About four months ago, Maiden Voyage, an album of Iron Maiden radio recordings from the 1980s, popped up for sale on Coda Records’ website without the storied metal band’s permission. Andrew Wyllie, Iron Maiden’s head of business affairs, contacted the act’s labels, BMG and Warner Music, for help persuading the U.K. retailer to pull down the unauthorized album — with, he says, no success. His next call went to Corsearch.

The 75-year-old brand-protection company, which fights bootleggers using artificial intelligence, image-matching software and automated takedown notices on retail sites like Amazon, Etsy and eBay, quickly ended the sale of Maiden Voyage and social media ads for it and was “more effective in getting those records taken down than our record company,” Wyllie says. “They’ve definitely affected the bottom line.”

(A Coda rep says the store removed Maiden Voyage after hearing from Iron Maiden, the process was “very straightforward” and “we’re happy just to take stuff down if there’s a problem.”)

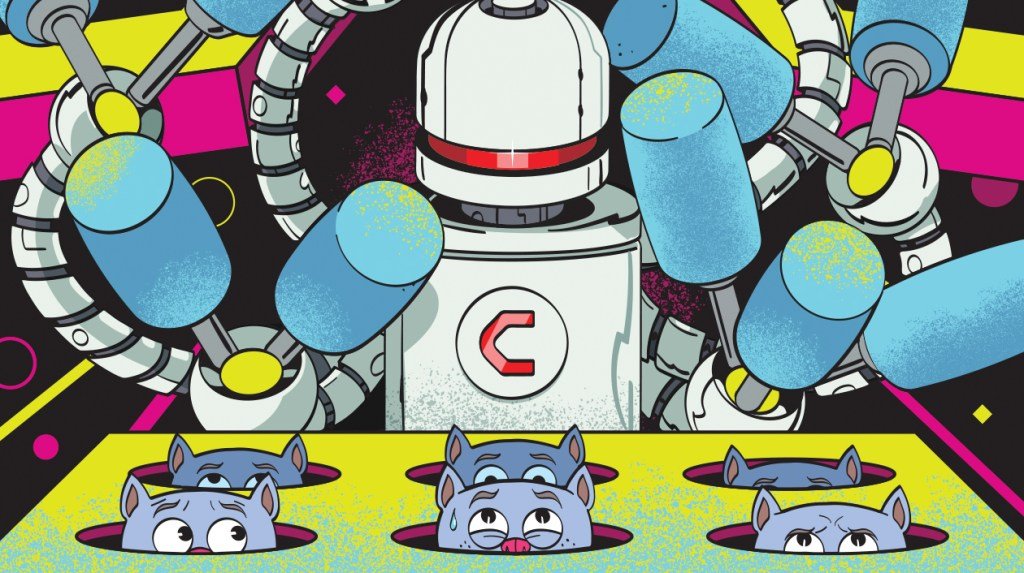

For a long time, artists, managers, labels and merchandise companies have likened online bootleg sales to a game of Whac-A-Mole: When attorneys send cease-and-desist notices to unauthorized and knock-off merch retailers, the seller reemerges elsewhere. But in recent years, companies such as Corsearch and rival CounterFind have used more sophisticated methods to protect their music-business clients. They remove tens of thousands of online listings every month, hire regional attorneys to invoke the U.S. trademark statute known as the Lanham Act and prosecute violators.

“It’s scientific, it’s strategic and there are solutions,” says Eric Cohen, founder of TZU Strategies, which collaborates with Corsearch and claims to have removed 55,000 counterfeit listings on behalf of top music stars. Using “robust” technology, he says, “we are able to connect a large majority of the counterfeiters that are using multiple accounts selling on multiple platforms in multiple ways.”

Corsearch has 450 employees and 5,000 clients, including A-list artists and music companies. “We work with law enforcement we’ve had relationships with for 15 years,” vp of enforcement Joe Cherayath says.

Dallas-based CounterFind is more of a “boutique” company, says co-founder and head of business development Rachel Aronson. In 2017, the founders were working with Linkin Park when frontman Chester Bennington died and, as Aronson recalls, “An insane amount of counterfeit merch was popping up all over the place.” CounterFind removed “millions of dollars in counterfeit products from the market in one weekend,” she says.

Since then, CounterFind has expanded to 30 employees and works with Bravado, the merch company owned by Universal Music Group (UMG) that represents Ariana Grande, Billie Eilish and dozens of other artists. “The majority of these major counterfeiters are working from their couches overseas and they’re creating print-on-demand products,” Aronson says.

Music bootlegging and counterfeiting is big business. Last year, U.S. Border and Customs Protection seized nearly $2.8 billion in copyright-infringing goods shipped from countries like China, Turkey and Canada. Jeff Jampol, whose company, JAM Inc., manages the estates of The Doors, Janis Joplin and others, estimates these unauthorized sellers cost artists roughly $20,000 to $50,000 for every $1 million in yearly T-shirt sales. “It’s kind of endless,” says Rick Sales, longtime manager for Slayer, Ghost, Mastodon and others. “It’s like, ‘How long is a piece of string?’”

Bravado’s president, Matt Young, adds that Counterfind and Universal Music’s in-house intellectual-property-protection team have been “proactive” and UMG artists and managers appreciate the company’s reports showing all the takedowns they’ve achieved of unauthorized material online. But “it kind of still is like Whac-A-Mole,” he says: Amazon has been “great” at strengthening its protocols to fight against bootleggers, but “these marketplaces don’t really care where this business comes from,” and “if you Google any artists, the first several things you see would be pirated goods.”

Representatives for Corsearch and CounterFind disagree. Aronson describes a repeat offender who was “basically scraping and copying an artist’s entire merch site” using a website address with one letter removed from the official URL. After months of reporting the bootlegger through its multiple hosting providers, CounterFind employed the Lanham Act to permanently remove the site and domain. In April, Corsearch worked with police in China to raid warehouses belonging to alleged online counterfeiter Pandabuy and seized millions of packages about to be shipped to customers. “The key point,” Cherayath says, “is not to stop at cease-and-desist — that’s just one of the mechanisms in the enforcement strategy.”

In addition to scouring the internet for unauthorized merch sellers and providing data to the band about where counterfeiters are located, Corsearch helps Iron Maiden discern which t-shirt manufacturers are bootleg operations and which are harmless fans who design their own apparel for a few extra bucks. The Corsearch system also allows the band’s management to respond to fans’ tips and identify bootleggers and counterfeiters based on complaints — like the Facebook scammers who promise VIP tickets and backstage access with a $500 click.

“It’s the bane of my life. As soon as we announce a tour, the bootleggers online have already stolen the image from a tour poster and put it on a t-shirt in five minutes,” Wyllie says. “The Corsearch system almost pays for itself. You’re not having to use local attorneys and you’re getting to the root of the problem pretty quickly.”

A version of this story appears in the June 8, 2024, issue of Billboard.